Organic Evolution in terms of the Implicate and Explicate Orders.

Part LXII

Hymenoptera (wasps, bees, ants) (Sequel)

The evolutionary diversification in the Order Hymenoptera in terms of Strategies (Sequel).

Evolutionary establisment of the Bees (Apoidea)

Primary-apoine Phase of the Vespoid Type

In Masaridae we can also observe a further development of the newly-born instincts toward the typical apoine ones. In the beginning the honey-food given off from the mother-wasp's mouth, naturally was fairly juicy and delicate, and could therefore, in these [evolutionary] starting conditions, not being stored in a large quantity in the cells. Subsequently, however, with the corresponding adaptation of the organism of the mother-wasp, and first of all of her mouth-organs, to collect flower-pollen, she began feeding her larvae with more dense and concentrated food abundantly containing flower-pollen rich in proteines. This transition of the consistency of the food carried into the cell also gave the mother-wasp the possibility to relinquish the original method of step-by-step feeding of the larva, and to pass over to a new one -- preparation in the cell of honey-provisions for the larva in a speeded-up way in a quantity sufficient for the whole of the larva's period of feeding and growth.

In this respect the nesting-behavior of the gayella's -- a peculiar group of masarids, sometimes taken to represent a subfamily, the Gayellinae -- is very indicative. The only species of them, encountered in Chile, Gayella eumenoides Spin., constructs, according to observations of Claude-Joseph, 1928, its nests out of mineral cement on steep surfaces of stony blocks and projections from rocks. See next Figure.

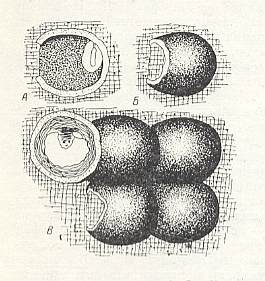

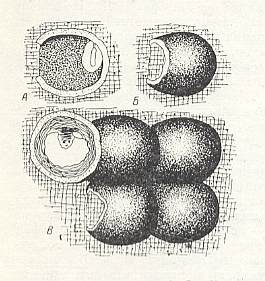

Figure 2 : Nest of the masarid Gayella eumenoides Spin.

Upper left -- A cell provided with honey-provisions (section), with the egg suspended in the depth of the cell.

Upper right -- A still empty cell.

Bottom -- A fully-grown larva [white] in a cell.

(After CLAUDE-JOSEPH, 1930, in MALYSHEV, 1966)

The shape of a cell is dome-like with a wide entrance opening at one of the sides contiguous to the substrate. The egg is laid before provisions are prepared. In this the female suspends herself from the vaults of the cell such that her head is turned to the entrance opening, and the tip of her abdomen, touching the ceiling of the cell, secretes a sticky droplet that instantly solidifies. The egg gradually appears, keeping track with the downward motion of the abdomen, and remains suspended from the vault on a thread. All this recalls the method of the Odynerus (Eumenidae) which also suspend the egg from the ceiling of the cell. Having laid the egg, the wasp visits flowers of certain plants and collects from them pollen and nectar with the help of the extremely developed, divided in two at the end, tonguelet recalling the tonguelet of primitive bees. She stays here for about a quarter of an hour in order for one load to be collected, a load that must then be brought to the cell, and is busy for 5 to 10 minutes to unite the load to the provisions brought in earlier. In such conditions the preparation of a complete ration for one single larva takes no less than three days. As a result of this work a dense and very tough honey-dough fills the whole cell except for a small brood-chamber, where the egg remains suspended without any contact with the provisions. When provisioning is concluded, the cell is closed and the to this purpose constructed wall usually will serve as the bottom [rear wall] for the next cell (see Figure above).

The emergence from the egg takes place two weeks after oviposition, and, consequently, long after the provisions in the cell were concluded. Feeding and growth of the larva takes many months and are interrupted only by short periods of rest. Defecation by the larvae takes place only after the provisions are consumed. After a period of deep rest, lasting for several weeks, the larva, having concluded feeding, takes to preparing a cocoon, consisting of many concentric boxes. This work takes many months. The whole life-cycle of Gayella eumenoides Spin. lasts, evidently, two years. Therefore at the hight of nesting we may already find larvae enclosed in their complex cocoons. The emergence of the adult takes place in November and December.

To such a long duration of the masarid development, sometimes extended to three years, also other investigators did point. But when the cause of such a slowing-down of development might be seen to be the unfavorable influence of the dry season in the region Kappu in South-Africa, we can hardly say this with respect to Gayella eumenoides Spin., their nests normally being covered with a layer of snow for long months in the mountains of Chile. The cause of this slowing-down of development of the masarids must be sought for in the difficulty of physiological adaptation of their larvae to their new dense vegetable food, having replaced the original animal food of their ancestors.

Here we must also think of those sparse data referring to the nesting behavior of Celonites abbreviatus Vill. in the south of France. This masarid constructs its free, cylindrical, cells, rounded off at the end, adhering them to dry stems of plants or to individual stones or rocks. Fine earth or dust serve as building material mixed with saliva of the female builder. C. abbreviatus Vill., as Ferton reports, begins the construction of the cell from its very upper end, that is, from the bottom of the cell having usually turned its bottom up. One cell, being observed in the middle of June, contained a white honey-dough, filling the lower part of the cell, and the small larva had positioned itself onto the provisions -- which fact demonstrates that the egg was deposited before provisions were prepared [because the development in the egg, which takes considerable time, was already concluded, and the larva hatched].

In another similar case such an upside-down cell contained an egg which was placed in the upper part of the cell-cavity, on the upper surface of the honey-dough. In another cell a very small larva was lying on the honey on its upper surface. All this, of course, strongly reminds us of the method of preparing provisions described for Gayella eumenoides.

Massive preparation of honey-provisions is, apparently, also typical of some other masarids building their nests on the surface of objects, as for instance Pseudomasaris vespoides Cress., P. edvarsii Cress., Masaris vespiformes F. Unfortunately, relevant data are very scanty.

Thus, deposition of the egg in the still empty cell with subsequent preparation in this cell of dense, not flowing, honey-provisions, behind which there remains room for the egg ("brood-chamber"), -- all these are characteristic features of the primary-apoine phase of the vespoid type, just described.

The next apoine phase will be described in the next document.

e-mail :  ( Please write in ' Subject ' entry : ' METAPHYSICS ', in order for me to be able to distinguish your mail from spam )

( Please write in ' Subject ' entry : ' METAPHYSICS ', in order for me to be able to distinguish your mail from spam )

To continue click HERE for the further study of Organic Evolution, Part LXIII.

Back to Homepage

Back to Contents

Back to Evolutionary Part XIV

Back to Evolutionary Part XV

Back to Evolutionary Part XVI

Back to Evolutionary Part XVII

Back to Evolutionary Part XVIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XIX

Back to Evolutionary Part XX

Back to Evolutionary Part XXI

Back to Evolutionary Part XXII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXIV

Back to Evolutionary Part XXV-A

Back to Evolutionary Part XXV-B

Back to Evolutionary Part XXV-C

Back to Evolutionary Part XXVI

Back to Evolutionary Part XXVII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXVIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXVIII-A

Back to Evolutionary Part XXIX

Back to Evolutionary Part XXX

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXI

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXIV

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXV

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXVI

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXVII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXVIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXIX

Back to Evolutionary Part XL

Back to Evolutionary Part XLI

Back to Evolutionary Part XLII

Back to Evolutionary Part XLIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XLIV

Back to Evolutionary Part XLV

Back to Evolutionary Part XLVI

Back to Evolutionary Part XLVII

Back to Evolutionary Part XLVIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XLIX

Back to Evolutionary Part L

Back to Evolutionary Part LI

Back to Evolutionary Part LII

Back to Evolutionary Part LIII

Back to Evolutionary Part LIV

Back to Evolutionary Part LV

Back to Evolutionary Part LVI

Back to Evolutionary Part LVII

Back to Evolutionary Part LVIII

Back to Evolutionary Part LIX

Back to Evolutionary Part LXa

Back to Evolutionary Part LXb

Back to Evolutionary Part LXc

Back to Evolutionary Part LXI

( Please write in ' Subject ' entry : ' METAPHYSICS ', in order for me to be able to distinguish your mail from spam )

( Please write in ' Subject ' entry : ' METAPHYSICS ', in order for me to be able to distinguish your mail from spam )