We have now, finally, come to the last major group of Hymenoptera, the bees (flower-wasps, Apoidea). Following Malyshev, 1966, we will discuss their origin and evolution, and their difference from other groups of Hymenoptera.

Hypotheses and position of the question of the origin of bees.

Close analysis showed that the origin of the superfamily of bees (Apoidea), rearing their larvae not with animal food, as it is characteristic of wasps, but with nectar and pollen of flowers, is among the darkest questions about the evolution of the Hymenoptera.

It is true, already Müller, 1872, in his well-known work "Application of Darwin's doctrine to the bees", demonstrated that the bees originated from "digger-wasps" (Fossores of the earlier authors). He based all this chiefly on morphological similarity being present between the lower bees and some of the mentioned wasps, such [morphological features] as : slender, narrow body, mouth-parts, and also -- as a result of a not-yet-developed hairy coat -- a shiny surface. He also pointed to the similarity of feeding instincts in the adults in both of them.

With respect to the question in what way might has taken place the very transformation of vespine [wasp-like] habits into apoine [bee-like] ones, he writes : "Digger-wasps, which themselves (that is, in their adult state, -- C. Malyshev) feed on honey and pollen, could easily throw up this substance swallowed in abundance (that can be seen when an individual, just taken from a flower, is squeezed between the fingers), and so could replace, partly or totally according to need, collecting living prey by the abundance of true feeding". Such a change, the investigator assumes, "would be highly useful to the adults as well as to the young, because for feeding a single larva, significantly less (three times, that is) weight of flower pollen and honey is needed than of insects or spiders". But despite this statment, the concrete path taken in the origin of bees remained obscure.

From that time onwards it was firmly established, on the basis of morphological data, that the bees indeed had evolved from wasps, and that they thereby are most closely related to the so-called digger-wasps, that is, to the sphecoid wasps. In fact, the mentioned group of wasps, as a whole, in its structure differs from bees, according to the latest investigations of Michiner, 1944, only by the absence of forked hairs and the structure of the hind-heels (basitarsi), that are in wasps usually not flattened and not broader than the next segments of the foot (tarsus), as it is observed in bees. From this, according to Michiner, in the classification of the Hymenoptera "we should place the bees as a part of the superfamily of digger-wasps (Sphecoidea), while placing them as an independent superfamily of bees (Apoidea), distinguished from Sphecoidea, obscures the true kinship between both groups. Or we might recognize a higher [taxonomic] category than superfamily in which to unite these two groups".

As to the second group of wasps, the so-called vespoids (Vespoidea), the bees stand farther away from them, and differ from them in that the shoulder-outgrowths of the prothorax in bees (as in digger-wasps) do not reach the wing-base, while the pronotum (dorsal shield of prothorax) of the vespoid wasps is more strongly developed, more deeply incised posteriorly and its shoulder outgrowths reaching the base of the wing-scales (tegulae). Because of this basic morphological difference, placing the bees directly adjacent to the vespoid wasps is problematic.

A wholly unusual view about the genealogic relationships of the bees was given by Börner, 1919. Departing from the fact that digger-wasps (Sphecoidea), as well as spider-wasps (Pompilidae) of the vespoid wasps, carry on their hindlegs a "make-up apparatus" (Hinterbeinputzburste), and also special vesicles on the soles (Sohlenbläschen), Böner rejects the generally-agreed division of the wasps into the mentioned two groups, that is, Sphecoidea and Vespoidea.

By the term "make-up apparatus" we here signify a brush of which the hairs increase in length toward the base of the heel. On the other hand, they shorten (as on the middle legs) when there is no "make-up apparatus" present.

Then, on the basis of the fact that bees and ants, and also the scolia's (Scoliidae) of the vespoids, do not possess this "make-up apparatus" on their hindlegs, the mentioned author takes it as inadmissible to suppose that they had lost it, while once having possessed it [So it is here supposed that the absence of the make-up apparatus is a primitive feature, that is, an original feature. They never possessed it].

As to the characteristic feature -- the spatial situation between the lateral outgrowths of the pronotum and the wing-base, Börner, because of some variability of the lateral span of these outgrowths in wasps and bees, does not give it decisive significance. On the basis of these data he concludes that bees are related to ants, and not to wasps. However, this position was not confirmed by subsequent researchers, but on the contrary, was taken as false as a result of the misinterpretation by Börner of the totally derived nature of these features on which he based his conclusions.

Later it will become clear that the bees developed along totally different lines, and that placing them close to the ants has no basis at all.

Recognizing, consequently, the real close kinship of the bees with the sphecoid wasps, it is held, according to Michiner, 1944, that among recent representatives of the digger-wasps are not preserved those that directly gave rise, at the time, to bees. Despite this actual state of affairs, Friese, 1892, 1923, and then Buttel-Reepen, 1903, and others, attempting to get closer to the solution of the problem, place at the base of the genealogic tree of the bees one or other [already] determined genera of digger-wasps -- Passaloecus, Diodontus, Crossocerus, and also Tachytes and Astata. However, all these wasps, only by superficial characters being similar to certain bees, are, with respect to their maternal instincts, on the contrary, true "digger-wasps" : They not only do not prepare in cells honey-dough, but place in them prey, consisting of these or those insects, massively, and deposit the egg onto the prey, which also serves as food for their larvae. And so, in a number of other authors, Friese included, touching on, or particularly adressing the problem of the evolution of the aculeate Hymenoptera, the question of the origin of the instincts of the bees remained, essentially, open, or was not at all dealt with.

This question, however, is so interesting that it deserves a special analysis of the phenomena here concerned, the more so because we have the possibility to get to its solution from different angles, and first of all see in what way nature herself had solved a similar problem in another group of aculeate Hymenoptera, namely in vespoid wasps, where again the morphological affinity of typical wasps and forms with habits of the apoine type [bee type] is beyond doubt.

Introductory Summary concerning the origin of Bees

The following discussion, by Malyshev, of the evolutionary (pre-)phases of bees (Hymenoptera-Aculeata, Apoidea) [reproduced in this and the next four documents of the present website] evident in existing (true) wasps, is more or less complicated. It is therefore wise letting it precede by an introductory summary.

The mentioned (pre-)phases discussed in Malyshev's book are the following :

In finding the evolutionary roots of bees, instead of focussing on mere morphological characters, Malyshev concentrates on instincts, namely instincts of nursing the larvae (nature of food, and way of offering it to them), and instincts of nest-building. The instincts of bees can be found already in "true wasps" which latter term refers to the aculeate wasps, wasps that is, having their ovipositor transformed into a sting. So the terebrant hymenoptera ('hymenoptera parasitica') -- and, of course, also the saw-flies (hymenoptera symphyta) -- are not 'true wasps'. The group of true wasps mainly consists of 'sphecoid wasps' (digger-wasps) and 'vespoid wasps' (other solitary wasps, plaited-winged wasps [including the social wasps] ).

Malyshev concentrates on the very origin of bees. He does not discuss the origin in bees of social life. Many species of bees, being certainly the most primitive of them, are solitary.

Bee-habits as they originate in true wasps

APOINE PHASES (fully discussed in present and following documents) :

Hemi-apoine Phase in vespoid wasps.

Feeding the larvae with honey-food (instead of preys) first of all presupposes the presence of a cell in which provisions are placed and where the feeding of the wasp-larva takes place.

First wasp-phase ( Primary-vespine (pompiloid) phase ) : Catching prey before cell-building. This is still too far away from bee-habits.

Second wasp-phase ( Secondary-vespine (sphecoid) phase ) : First cell, then one prey being placed in it (one dose), is also still too far away from true bee-habits.

Third wasp-phase ( Third vespine (crabroid) phase ) : First cell, then mass-providing of several preys.

Fourth wasp-phase ( Fourth vespine (Bembecoid) phase ) : First cell, then gradual (succesive) providing. And even also this phase (and with it the 3rd phase) needs several further intermediate phases to finally yield bee-habits.

Fifth wasp-phase ( Fifth vespine (moneduloid) phase ) : (Eumenidae and others), egg not deposited onto prey, but on the wall of the still empty cell. But also here (5th phase) the immediate transition from animal food to honey+pollen food is not yet possible.

Only in the Sixth wasp-phase ( Newly vespine (vespoid) phase ) of the evolution of vespine instincts are conditions visible allowing further development -- the transition from vespine instincts to apoine instincts [bee-instincts] : gradual, successive feeding of the larvae having hatched from eggs having been deposited into the still empty cell, [feeding] not with a whole prey, but as chewed, and having to hand over the food directly to the mouth of the larva. And so it became possible to give the larva the same food as was had [i.e. consumed] by the mother-wasp herself : nectar and pollen from flowers. Here three wasp families [in the taxonomical sense] are relevant : Masaridae, Eumenidae, and Vespidae. But it is the Masaridae that are the most important in this respect. Like the Eumenidae, they are plaited-winged solitary true wasps.

Primary-apoine Phase of the vespoid type.

Development of apoine habits went further in Masaridae, especially, or at least, in the subfamily Gayellinae. This development consists in the h i g h e r concentration of the pollen-food, now making possible to provide the cell with a consistent mass of (honey) food sufficient for the whole period of larval growth. Thus, depositing of the egg in a still empty cell with a subsequent preparation in that cell of compact, not fluid, honey-provisions, behind which [provisions] room is left for the egg. All this constitutes the set of characteristic features of the Primary-apoine phase of the vespoid type.

Secondary-apoine phase of the vespoid type.

To understand the subsequent evolution of the nesting-instincts of the Masaridae, still more approaching the apoine type, the habits of Ceramius tuberculifer Gauss. are instructive. But the nesting instincts of this species (or of C. lusitanicus Klug.) still differ from the pure apoine instincts. But this difference, however, is not so essential as to not reckon (these) Masarids, as to their nesting behavior, also as being bees, but special bees, still preserving a characteristic trait of their vespoid ancestors -- depositing eggs before preparing provisions.

The habits of the investigated Masarids viz., preliminary deposition of the egg in an empty cell, subsequent preparation of specially formed honey-provisions, and then carrying the egg onto these provisions, form the chief biological feature of the secondary-apoine phase of the vespoid type. As far as was possible to establish, the evolution of the instincts of the masarids was concluded with this phase. But in the light of what was expounded we may assume also a further transformation of them with respect to typically apoine habits. It may have proceeded in virtue of a certain simplification : By way of cancellation of the act of preliminary deposition of the egg in the empty cell, and, connected with this, the subsequent transposition of the egg onto provisions prepared earlier. Accordingly, in this new supposed phase the egg must be deposited after the preparation and formation of the honey-bun onto the wall of the cell next to the provisions.

Also nest-building is further developed. As a result the ability to construct a cap of the cells changed into the ability to model the cell, as it already appeared in Odynerus, and especially in masarids.

Evolution of the sphecoid wasps (digger-wasps) and the question of the (evolutionary) establishment of true bees.

While in vespoid wasps we encounter bee-like forms (Masaridae), in sphecoid wasps we encounter true bees (that is, from the sphecoids true bees develop).

Sphecoid wasps, as to their morphological features, are more specialized than the vespoid wasps. We can even say that, as to the construction of their thorax, they differ from all other Hymenoptera and come close exclusively to true bees. For all this, we have to have a closer look to, especially, the wasps of the genus Microbembex (Sphecoidea-Bembecidae), after having followed the line leading to them.

(End of introductory summary on the origin of bees)

Hemi-apoine Phase in Vespoid Wasps.

The evolution of the way of life and of instincts of the Hymenoptera in its first stages of development (among saw-flies, horn-tails, terebrants) has led these insects, as having expounded earlier, to that particular stage, at which, having, as to their morphological features, become wasp-like [that is, having acquired the typical vespine morphology], the mentioned hymenoptera still had primitive instincts, definitely close to the maternal instincts of their terebrant ancestors [Recall, that the Order Hymenoptera consists of three suborders, viz., the Symphyta (saw-flies and allies), the Terebrantia (parasitic hymenoptera, such as ichneumon flies), and the Aculeata (sting-carrying hymenoptera, such as true wasps, ants, and bees)]. But this was still the preliminary semi-vespine phase in the evolutionary developmental path of the wasps. After this, a new series of phases followed, that finally have given the higher forms of vespine life.

Among the multitude of diverse wasps, populating the world, only in one group of closely related vespoid forms, namely among the so-called plaited-winged wasps (Diploptera) we find habits of the apoine type. Today we may definitely hold that depositing the egg in a still empty cell before bringing into it provisions, is the chief biological trait of all plaited-winged wasps. Only from the base of this characteristic biological feature, as will be explained later, may originate, among them, the habit of raising the larvae with honey-food. An absolute prerequisite for this was, however, yet a second remarkable trait of some of the plaited-winged wasps, namely feeding the larvae with chewed [to pieces] prey.

In the evolution of instincts in vespine hymenoptera, the habit of laying the egg in the [still] empty cell, as was told earlier, was reached only in the two last phases of development of vespine behavior. The unification of this instinct with that of bringing the larva chewed prey, appeared only in the very last phase, the newly-vespine phase among the higher eumenids and in vespids [both being vespoids]. This demonstrates that the appearance of habits of the apoine type among Diploptera must have been preceded by a complex history.

Indeed, feeding the larvae with honey-food first of all presupposes the presence of a cell as a special room whereto these provisions are brought and where feeding of the wasp-larva takes place. From here it becomes clear that the first phase of vespine life ( Primary-vespine (pompiloid) phase ), in which provisions (prey) were obtained before constructing the cell, was still too far away from apoine habits (bee-habits). We know, that providing the cells with honey-dough, there where it generally takes place, always is done, not in one, but in several doses. Therefore also the second stage, 2nd phase ( Secondary-vespine (sphecoid) phase ), in the development of the instincts in wasps, where in an earlier-prepared cell only one prey is placed, and in one dose, was still far away from true apoine habits.

In the next two phases (3rd and 4th) the act of provisioning the cells became a multiply repeated act, such that into an earlier constructed cell already several preys were brought in, either in the accelerated massive way as in the 3rd phase ( Third vespine (crabroid) phase ), or in the slowed-down way, according to need, "progressive" as in the 4th phase ( Fourth vespine (Bembecoid) phase ). The egg, as formerly, was deposited definitely onto the prey, and in a strictly determined way. With such states of affairs we cannot hold that these predatory habits of the wasps might directly, without going through any intermediate stages, be replaced by apoine habits.

Down to a further development of vespine instincts, where the egg became deposited not onto the prey, but on the wall of the still empty cell, first of all went plaited-winged wasps (of the family Eumenidae), but not only they alone. However, the difficulty of a direct replacement of animal food by vegetable food -- a mixture of honey and pollen in provisioning the cells -- was still there. It consisted in the necessity of a profound change of habits of the mother-wasp, when she would have to leave her predatory habits and replace them by collecting honey and pollen. In addition this difficulty included the fact that the wasp now had, instead of simply handing over the prey to the larva, offer it new liquid or semiliquid food in such a way as to not wet its body and not clog its spiracles, that is, offering it directly into its mouth. Such a deep change of behavior of the mother-wasp cannot be assumed. So also this phase (the 5th) cannot be the stage, that had directly determined the apoine habits.

Only in the highest phase, the 6th phase ( Newly vespine (vespoid) phase ), of the evolution of vespine instincts are conditions visible that lead to the for us most important point -- the transformation of vespine instincts into apoine instincts. Precisely in the fact of slowed-down (piecemeal) feeding of the larva, having hatched from the egg deposited in the empty cell, the mother-wasp acquired the possibility to bring to the larva a prey, not in one piece, as it was the case until now, but in a chewed [to pieces] form, not allowing it to place in the cell, but, on the contrary, demanding it to offer straight to the mouth of the larva. And here then on the basis of precisely this instinct also originated, one has to assume, among plaited-winged wasps, a new manner of feeding the larvae by them : not with other insects, but with that what the mother-wasp herself eats, that is, with nectar and pollen of flowers. In a stronger or lesser degree mixed with this new food was, naturally, the mother's saliva. And precisely this food, at least in the beginning, was given directly from the mouth of the mother into or toward the mouth of the larva. Such a transition the more easily was allowed to be accomplished by the fact that wasps, as is known, eagerly have a nibble of sweet vegetable sap and often are found on flowers with nectarines accessible to them, to which fact also pointed Hermann Müller (1872).

It is interesting to see in what way today feeding the larvae with honey-food appears in plaited-winged wasps. There exist indications of rearing the larvae with nectar and flower pollen in all three families into which one usually divides the plaited-winged wasps : among the Masaridae, the Eumenidae, and the social wasps (Vespidae). But these indications are not equivalent. Thus, one must assume that in social wasps (the genera Nectarina and Polistes), undoubtedly, already further complexifications of instincts have taken place as to the care of the young, and in addition, data on their biology are still insufficient, as it is also stated in the literature. As to the Eumenidae, there is only one article known to the author in which the provisioning of the cells with flower pollen is noted for wasps of the genus Zethus, but without reference to the ultimate source and without indication of the very species of these wasps.

Generally with respect to wasps of the genus Zethus it is known that they make free cells from small pieces of leaves, while alternating still incomplete construction of the cell with depositing an egg in it. Then they hunt for small caterpillars and feed them to their larva from day to day. With respect to one species (Zethus cyanopterus Sauss.) encountered in the Philippines, it is noted that caterpillars, brought to the larva were partly chewed by the mother. In our fauna (Soviet Union) the group Zethinae is represented by the genus Discoelius, about the nesting behavior of which there now exist definite data, pointing to their larvae being carnivorous.

The greatest interest for the clarification of the beginnings of the development among plaited-winged wasps of instincts of the apoine type shows the third family of them, the Masaridae.

Let us then turn to the factual material giving us the nesting-instincts of the masarids -- peculiar wasps, distributed almost exclusively in the subtropics.

The masarid fauna of the Soviet Union, being still little investigated, is represented by five genera : Masaris (3 species), Jugartia (1 species), Quartinia (7 formes), Celonites (12 forms), and Ceramius (1 species), distributed in Central Asia, Caucasus, and Trans-caucasus. Roubaud, 1916, assumes that the Masaridae did not at all go through the (evolutionary) stage of paralysators, and branched off from ancient Eumenidae earlier, before they had acquired the ability to paralyse a prey. However, the views of Roubaud about the evolution of instincts in wasps are fundamentally wrong, as it was already noted earlier.

Although articles on the biology of the masarids accumulated in the course of the century, the obtained data are until now insufficient, and what is most important, they for a large part deal only with the outer aspects of their life -- time of flight, mating, selecting a place for nesting, visiting of flowers, their parasites, and so on. Statements on the most important intimate points of their nesting behavior -- about deposition of the egg, about provisioning the cell, about rearing the larvae -- are absent in the majority of cases. This even also holds to articles of those authors which have the disposal of, as it seems, more than sufficient observational material, as for instance Brauns (1910, 1911).

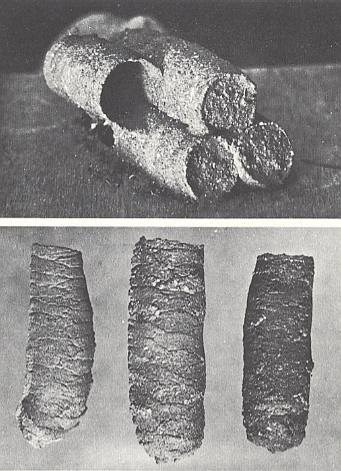

The next two photographs show cells made by a representative of the family Masaridae :

Figure 1 :

Above : Nest of Pseudomasaris edwardsii (Masaridae) with three completed, capped cells, and one incomplete cell.

Below : Individual cells of Pseudomasaris edwardsii are also seen to consist of overlapping half-arches, as in the very unrelated wasp Sceliphron, a remarkable example of evolutionary convergence.

(Photographs by Philip F. Torchio, in EVANS, 1973)

From available observations it nevertheless is clear that the masarids model cells of soil or clay giving them an independent shape -- cylindrical, oval, or semi-spherical -- and largely orient them either as tilted, or lying. In this they construct their nests either out in the open on the surface of stones, on rough rocks, on dry stems of plants, or nest in the soil in digged-out by themselves burrows in which they place their cells.

The next apoine phase will be described in the next document.

e-mail :

( Please write in ' Subject ' entry : ' METAPHYSICS ', in order for me to be able to distinguish your mail from spam )

( Please write in ' Subject ' entry : ' METAPHYSICS ', in order for me to be able to distinguish your mail from spam )

To continue click HERE for the further study of Organic Evolution, Part LXII.

Back to Evolutionary Part XVII

Back to Evolutionary Part XVIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXIV

Back to Evolutionary Part XXV-A

Back to Evolutionary Part XXV-B

Back to Evolutionary Part XXV-C

Back to Evolutionary Part XXVI

Back to Evolutionary Part XXVII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXVIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXVIII-A

Back to Evolutionary Part XXIX

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXI

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXIV

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXV

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXVI

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXVII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXVIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XXXIX

Back to Evolutionary Part XLII

Back to Evolutionary Part XLIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XLIV

Back to Evolutionary Part XLVI

Back to Evolutionary Part XLVII

Back to Evolutionary Part XLVIII

Back to Evolutionary Part XLIX

Back to Evolutionary Part LIII

Back to Evolutionary Part LVII

Back to Evolutionary Part LVIII