e-mail :

Sequel-2 to the Summary and Evaluation (of the documents XVI -- XXVIII concerning the promorphology of complex-shaped two-dimensional crystals).

This document (Part XXIX Sequel-2) appends a preliminary promorphological investigation that attempts the assessment of the promorph of (whole) p l a n t s, either having distichous (i.e. alternate), polystichous (i.e. whorled) or astichous (i.e. spiral) phyllotaxis (which are the main types of phyllotaxis in plants). This investigation is prompted by the considerations of the previous document, about pattern formation in crystals and organisms, and will again compare the generative field, as it is present in the process of leaf arrangement in plants, and (as it is present) in the process of crystallization. As such this investigation paves the way for a more extensive study of crystal analogies (i.e. analogies between crystals and organisms) and the ontological assessment of shape, symmetry and promorph, and of several other categories ( If / Then constants).

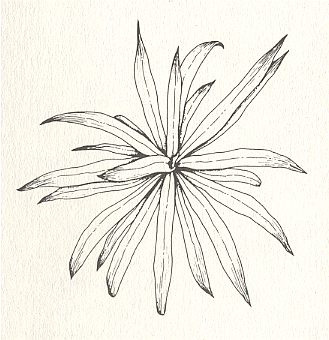

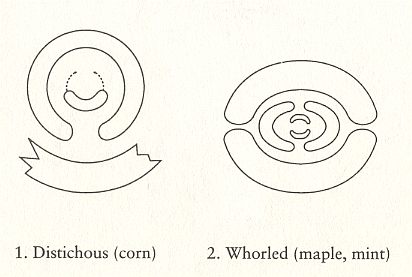

There are about 250000 different species of higher plants. They consist of roots, stems and leaves. If flowers do occur, then the organs of them, namely their sepals, petals, stamens and carpels, are in fact transformed leaves. So, when generally speaking, we can just use the term "leaves". Well, these leaves turn out to be arranged along the plant's stem in very definite ways, giving plants diverse appearances. But despite the enormous number of plant species, there are only three main types of phyllotaxis (three main types of leaf arrangement), viz., alternate, whorled and spiral. The next Figures give examples.

Let us describe, not (yet) explain, these three types of plant phyllotaxis.

To understand the position and distribution of the stichies (i.e. the lines, running along the length-dimension of the branch or stem, and connecting leaf attachment points, or primordia), we must realize that the growing branch or stem is geometrically a (long) cone :

Figure above :

Left image : Schematic representation of the growing tip of a plant stem. It is, geometrically, a cone. The blue dots indicate the position of the leaf primordia (which become leaf attachment points). The red line connecting these dots represents a stichy (S) (while plants normally have more than one stichy, here only one is drawn).

Right image : Enlarged top view of the growing tip. The stichy (S) now represents itself as a radial line, connecting leaf attachment points.

Let us now insert the stichies into the images of the Figures given earlier (schematically representing a top view of the three phyllotaxis types) :

Figure above : The stichies (indicated as red lines, and seen in top view) as they are present in respectively alternate phyllotaxis (distichous phyllotaxis) and whorled phyllotaxis (polystichous phyllotaxis, in the present case, tetrastichous phyllotaxis). The stichies connect leaf attachment points, while going up along the stem or branch. Here they are seen as radial lines. In distichous phyllotaxis there are two stichies, while in tetrastichous phyllotaxis there are four stichies.

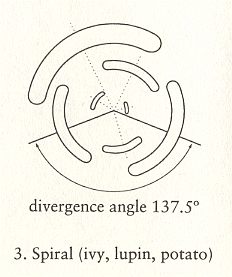

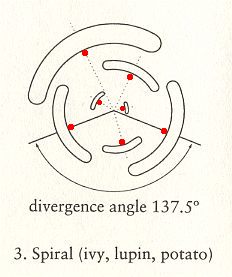

Figure above : Schematic representation of a top view of spiral phyllotaxis (astichous phyllotaxis). As can be seen, there are no stichies : Each leaf attachment point (indicated by a red dot) lies on a separate line running up along the stem, or, in other words, each leaf attachment point lies in a different radial plane of the growing stem. So none of these lines connect leaf attachment points, meaning that there are no stichies.

Before we shall describe a possible way these phyllotaxy patterns are actually generated in plants, and try to assess the latter's promorph, we first say some more about the geometric and arithmetic details of these patterns. Let's start with spiral phyllotaxis (astichous phyllotaxis).

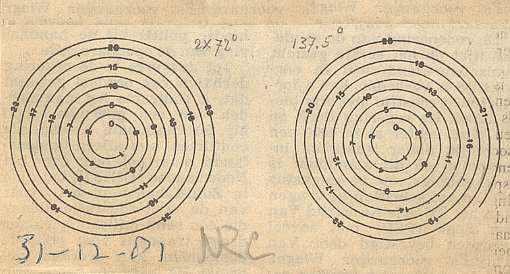

Figure above : Spiral of Archimedes. Among other things, it is the generative spiral according to the generation and migration of primordia in plants. In the left image the divergence angle between successive primordia is 1440, resulting in a five-fold distribution pattern (of primordia) consisting of five straight radii. In the right image the divergence angle is 137.50, resulting in a five-fold pattern with spiral radii (i.e. one family of five anticlockwise secondary spirals) (And, in addition to it there is at the same time another pattern of spiral radii representing a number of clockwise secondary spirals, and as such representing a second family of secondary spirals). The numbers of the left image (being badly visible) are again given in the next Figure.

Figure above : The numbers (which indicate te order of appearance of primordia on the generative spiral) of the left image of the above Figure are (again, but now more clearly) given.

The arrangement of leaves along the generative spiral automatically implies two intersecting families of secondary spirals, one family of clockwise wound, and another family of anticlockwise wound spirals, provided the divergence angle does not exactly divide a multiple of 3600. It is these secondary spirals that are picked out by the human eye (See the Figure above, right image , where one such secondary spiral is indicated). We can see them clearly in the patterns of florets -- tiny flowers that eventually become seeds -- in a giant sunflower, or in the patterns of scales in pineapples, but also in the arrangement of leaves on a branch of a Monkey Puzzle tree (See below). If the divergence angle does divide a multiple of 3600 exactly, then the leaves form, as seen from above, a system of radial lines, i.e. the secondary spirals are now straight lines (See the Figure above, left image ). In this case space (as seen from above) is not efficiently packed with leaves, because there are gaps. To fill the space efficiently, you need a divergence angle that does not exactly divide a multiple of 3600 (resulting in the pattern of leaf attachment points not to be periodic : If we go along the generative spiral no two leaves will exactly fall into the same radial plane). Or, for short, to fill space efficiently the divergence angle must be an irrational number, which is a number that cannot be written as the ratio of two whole numbers. Let me explain this further : An irrational number cannot produce a multiple of 360 by it being multiplied by a whole number, because if that would be the case, then it would be equal to the ratio of two rational numbers, and would then itself be a rational number : Let r1 be a whole number, and thus a rational number, and let r2 be a multiple of 360, which also is a whole number, and thus also a rational number. Let x be an irrational number. Then the above assumtion would read :

From this it follows that :

which is a rational number, because r1 and r2 are whole numbers.

So we need an irrational number for not letting any leaves to be superimposed upon each others as seen from above. But which irrational number?. Well, some irrational numbers are in a stronger sense irrational than other irrational numbers, meaning that they are harder to approximate by rational numbers. And the golden number, or equivalently, the golden angle, is the most irrational number, and so is expected to fill space most efficiently ( If we divide the perimeter of a circle into two parts, the lengths of which form a ratio equal to the golden number, which is 0.6180339 ..., or, exactly : (square root(5) - 1) / 2 ), the angle which is subtended by the shorter arc is the golden angle. It could be further expected that this most irrational of divergence angles, viz., an angle of 137.50776 ...0 , will be encoded in the DNA instructions of the plant, ensuring maximally efficient catch of light for its solar panels (leaves). However, it turns out that this need not to be so : It can be just a consequence of simple dynamics. But before we deal with that, we first elaborate further on the two families of secondary spirals that appear in spiral phyllotaxis.

In the next Figure the arrangement and sizes of successive leaves at the tip of a branch of the plant Araucaria excelsa, a species of Monkey Puzzle tree, is depicted. Successive leaves, i.e. leaves as they, one after the other, appear along the generative spiral, have been numbered, starting with the latest leaf, 1, in the sequence, then 2, 3, 4, 5, etc. The two families of secondary spirals (each such a spiral connects leafs that are in contact with each other) -- they are called parastichies -- are shown. They run in opposite directions. Now look at the number series along any such parastichy in the Figure below. One of these (starting at leaf 1) goes 1, 9, 17, 25, 33, 41, and so on. The difference between each successive number in this series is 8. Now look at the spiral running in the opposite direction -- 1, 14, 27, 40, 53, . . . . -- the difference is 13. This pattern is called (8, 13) phyllotaxy. In any individual case of spiral phyllotaxis we find one particular difference obtaining in every secondary clockwise spiral, and another such difference in any of its anticlockwise spirals. Moreover, these two numbers turn out always to be two consecutive Fibonacci numbers (i.e. consecutive with respect to the Fibonacci Series). Recall that the Series of Fibonacci numbers can be constructed by first setting up the numbers 1, 1, and then calculate the next numbers such that each of them is the sum of the two previous ones. So we get : 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, etc. And if we have of difference of 8 between the numbered members of a secondary spiral (as we had above), then there is room for 8 such spirals :

1, 9, 17, 25, 33, 41, etc.

2, 10, 18, 26, 34, 42, etc.

3, 11, 19, 27, 35, 43, etc.

4, 12, 20, 28, 36, 44, etc.

5, 13, 21, 29, 37, 45, etc.

6, 14, 22, 30, 38, 46, etc.

7, 15, 23, 31, 39, 47, etc.

8, 16, 24, 32, 40, 48, etc.

9, 17, 25, 33, 41, 49, etc. (which we already have)

So generally, if we have (a, b) phyllotaxy, then there are a secondary spirals running one way, and b secondary spirals running the other way.

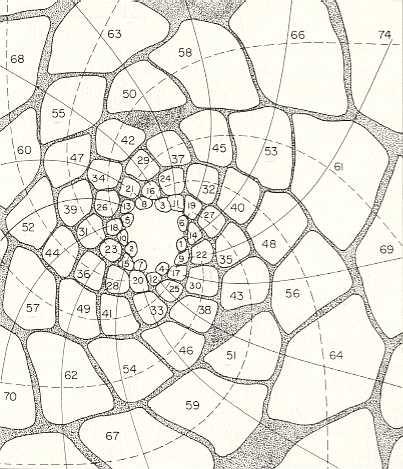

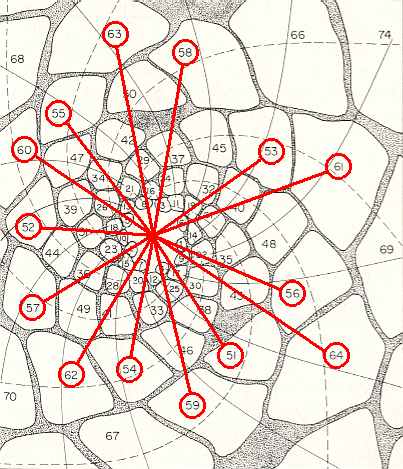

Figure above : Leaf arrangement on a branch of Araucaria excelsa. The leaves are numbered according to their successive apearance at the growing tip of the branch. The generative spiral is not directly visible because it is so tightly wound. The two families of secondary spirals (parastichies) are indicated, and connect leaves that are in contact with each other (while truly successive leaves are not in contact).

(After CHURCH, A., On the Relation of Phyllotaxis to Mechanical Laws, 1904. Again depicted in GOODWIN, B., 2001, How the Leopard Changed Its Spots)

In the next three Figures I have elaborated somewhat on the presence and invisibility of the generative spiral of the just depicted branch of Araucaria excelsa.

Figure above : Same as previous Figure. The golden angle (137.5...0). This angle obtains between successive leaves. So it obtains, for instance, between leaf 70 and leaf 69, and between leaf 69 and leaf 68, and then between leaf 68 and leaf 67, etc.

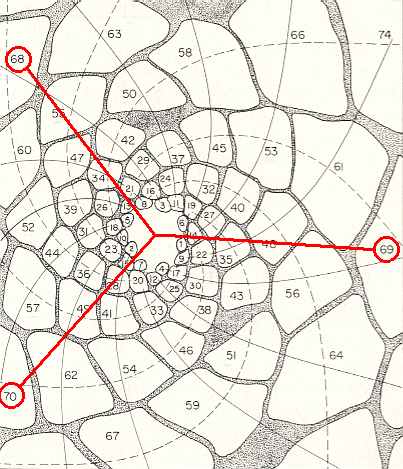

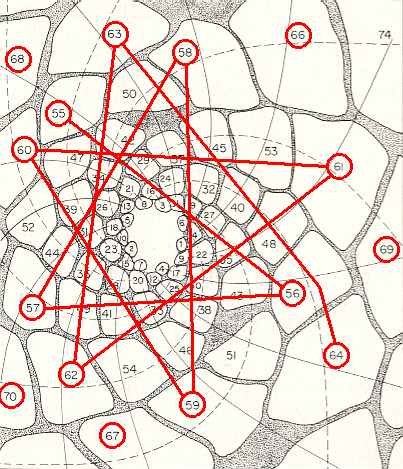

Figure above : Same as previous Figure. Here we follow a section of successive leaves (later leaf, lower number) : 64, 63, 62, 61, 60, 59, 58, 57, 56, 55. They should follow the generative spiral. We can see how hidden from view this spiral actually is.

Figure above : Same as previous Figure. Successive leaves 64 -- 51 connected by lines to the center of the growing tip. Again we can see how the generative spiral eludes visibility.

Now we will discuss a possible mechanism by which these Fibonacci numbers appear (as they do in Composite flowers, like daisies, sunflowers, etc., in pineapples, and in trees like the above Monkey Puzzle tree). It is enough to study the appearance and spatial arrangement of primordia as we see them emerge at the growing tip of a plant. A primordium is a bud from which a single leaf develops. The overall arrangement of the leaves that develop from these primordia is already fixed in the arrangement of the latter.

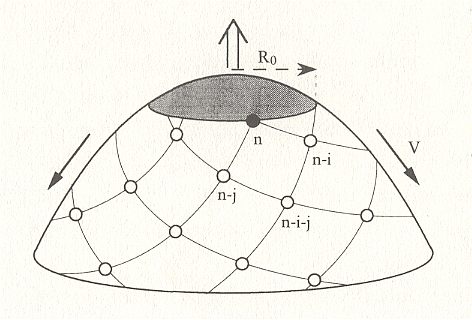

Figure above : Schematized representation of a meristem (growing tip) of a plant with spiral phyllotaxis, where primordia successively appear. R0 is the radius of the region that corresponds to the center of the meristem around which the leaf primordia are generated. The big vertical arrow symbolizes vertical growth of the branch or stem of the plant, while the laterally depicted arrows indicate the spatial expansion of the system of appeared primordia. i and j are pairs of successive Fibonacci numbers, i.e. such a pair of successive Fibonacci numbers is indicated as (i, j). The symbols n, n - i, n - j, n - i - j stand for numbers indicating the order of appearance of primordia along the generative spiral during growth. However, they'd better be symbolized by n, n + i, n + j, n + i + j . We see that consecutive numbers in one and the same family of secondary spirals display a constant difference between them. So for the anticlockwise family : (n + i) - n = i , which is a Fibonacci number. (n + i + j) - (n + j) = i , which is the same Fibonacci number. For the clockwise family : (n + j) - n = j , which is the second Fibonacci number. (n + i + j) - (n + i) = j , which is the same Fibonacci number. So here we have a case of (i, j) phyllotaxis.

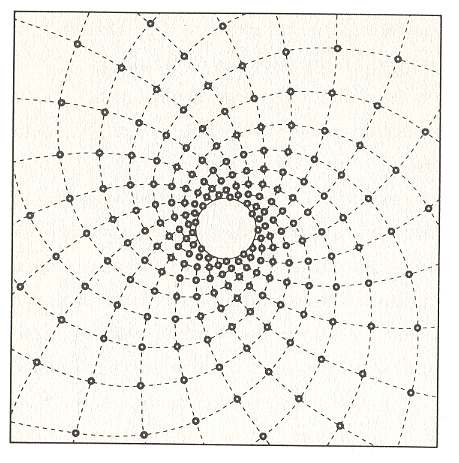

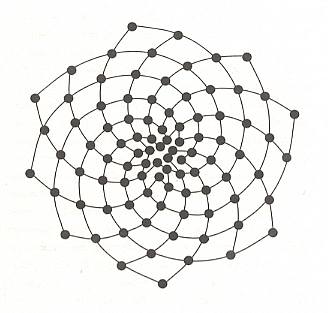

The next Figure gives the pattern of primordia / leaves that, in top view, shows (13, 21) phyllotaxis , i.e. there are thirteen secondary spirals going one way, and twenty-one the other.

Figure above : The spiral pattern of primordia/leaves obtained when i = 13 and j = 21, i.e. a case of (13, 21) phyllotaxy.

If the primordia appear s l o w l y, then by the time the next primordium appears, the only primordium that has any influence on it -- with respect to repelling each other -- is the immediately preceding one. The other primordia are too far away to have any effect. As a result, a newly appeared primordium is repelled to a position 1800 away from the previous one, so that the pattern produced is like alternate or distichous phyllotaxis, as in maize.

Whether the emerging phyllotaxis is distichous (i.e. alternate) or astichous (i.e. spiral) depends on the rate of appearance of successive primordia : Above some critical value of this rate distichous phyllotaxis transforms to astichous phyllotaxis.

Further change of this rate, while remaining above the critical value, determines which kind of spiral phyllotaxis we get in terms of consecutive Fibonacci numbers, i.e. we either get (1, 2) phyllotaxis, (2, 3) phyllotaxis, (3, 5) phyllotaxis, (5, 8) phyllotaxis, etc. And while the rate of appearance of primordia increases (as such representing different individual cases) the system of leaf arrangement quickly comes close to a 137.50 dovergence angle, i.e. if no particular circumstances happen to prevail, then this angle is being approched more and more for every individual case. Only when such particular circumstances happen to prevail we not only get other divergence angles, but also pairs (consisting of the two constant differences characterizing the two families of secondary spirals) that consist of two non-consecutive Fibonacci numbers, or even contain non-Fibonacci numbers. But all these are minority classes representing less robust, i.e. less stable, phyllotaxy patterns.

Over 80 percent of the 250000 or so species of higher plants have spiral phyllotaxis, with respect to leaves (as contrasted with the phyllotaxis of flower organs, like sepals, petals, etc.).

We now can easily describe the third type of phyllotaxis, namely whorled phyllotaxis (polystichous phyllotaxis). This would be obtained if more than one primordium were to appear at any one time in the growing meristem (growing tip of stem), with a rate of appearance below the above mentioned critical value, so that only the influence of the previous cluster of primordia were experienced. Then each cluster of primordia would take up positions at maximal distance from each other, and successive clusters would be arranged in the spaces of the previous cluster (because of their repellence), while also the members of such a cluster try to stand apart from each other as far as possible (also because of their mutual repellence). The result is whorled pattern. The number of primordia that appear simultaneously determines the radiateness of the resulting whorl, i.e. its homotypic number. As we know this number is often one from the Fibonacci series, but sometimes also other numbers, in particular the number 4 as we see in Crucifer flowers. The minimum number of elements (leaves or flower organs) a (single) whorl can have is two, as we see in Fuchsia (See in the Figure depicted earlier , left image). And this implies four stichies, because the whorls alternate. So this paricular case of polystichous phyllotaxis should be called tetrastichous phyllotaxis. Whorled phyllotaxis is most common in flowers and less so in the case of arragement of genuine leaves.

So all the patterns, viz., distichous (i.e. alternate), polystichous (i.e. whorled) and astichous (i.e. spiral) phyllotaxis, can be generated simply by changing growth rates and numbers of leaves (or sepals, petals, etc.) generated at any time. These are presumably the main parameters that differ among plant species.

So we get an interesting conjecture : the frequency of the different phyllotactic patterns in nature may simply reflect the relative probabilities [implied by the degree of dynamic stablity] of the morphogenetic trajectories of the various forms and have little to do with natural selection. That is to say, all the phyllotactic patterns may serve well enough for light-gathering by leaves and so are selectively neutral [Recall that flower organs are derived from genuine leaves] [Minimal covering of the leaves, however, is only the case where the phyllotaxis is spiral with a divergence angle of 137.5 . . . degrees]. Then it is the size of the domains [of stability] in the generative space of these generic forms that determines their differential abundance. This is not to deny that the forms taken by organisms and their parts contribute to the stability of their life cycles in particular habitats, which is what is addressed by natural selection. It is simply to note that an analysis of this dynamic stability of life cycles can never be complete without an understanding of the generative dynamics that produces organisms of particular forms, because their intrinsic stability properties may play a dominant role in determining their abundance and their persistence. The objective is not to separate these different aspects of life cycles, but to unify them in a dynamic analysis that puts natural selection into its proper context : it is in no sense a generator of biological forms, but it maybe involved in testing the stability of the form [and weeding out unstable forms that weaken the firmness of an organism].

Before we are going to determine the promorphs that are involved in these three types of phyllotaxis, we first consider briefly a comparison between the described process generating radiate organic structures (radiate in a broader sense, i.e. not only single whorls) according to these three types of phyllotaxis in higher plants, and the process that generates single radiate crystals.

As we have seen, the appearance of radiate structures in higher plants, is the result of a dynamical system, which has many potential trajectories to follow. Which trajectory will actually be followed, depends on the parameter settings of the system (where these settings could ultimately come from the genes) and initial conditions. Indeed the emergence of radiate structures in plants (to which we recken the structures that result from all three types of phyllotaxis) is what comes naturally : A medium, initially possessing a high degree of symmetry, becomes unstable (when growth leads to the generation of unstable initial morphologies -- which are therefore transient morphologies -- or unstable initial physiological states), which means that even very small perturbations will shove off the system to a new morphology (new structure) that represents a stable configuration under the circumstances. This new morphology generally has a lower symmetry than that of the original morphology. In phyllotaxis the ultimate elements that are going to interact with each other, resulting in a stable spatial distribution of them, viz. a phyllotaxis of leaves, sepals, petals, etc. as they are attached on a main axis, and thus forming a radiate structure, come from within the growing plant, i.e. they are generated in and by the meristem (while, of course, ultimately coming from without, as nutrient material). One by one, or cluster by cluster, they originate from a central well, so to say, and then migrate outward and repel each other, or, in other words they dynamically interact. They keep so interacting as long as they are under tension, i.e. as long as they are being pushed and pulled around by each other. Ultimately these elements will settle onto a stable pattern, where all tension has vanished. This pattern is, apart from totally irregular flowers, and apart from bilateral flowers, a radial structure (regular or amphitect). And it is on these strucures that we will concentrate, when comparing organic pattern formation with inorganic pattern formation. See next Figure.

The above structure, which is the result of (8, 13) phyllotaxis in the individual development of some higher plant, clearly is a regularly radiate structure. In fact, however, we see two radiate structures, i.e. two interlaced radial structures. One of them has C8 symmetry, while the other has C13 symmetry. As the Figure suggests, we could say that the elements of the structure (representing, for example, the florets of a giant sunflower, or the scales of a pineapple) are organized according to a deformed lattice, while in itself it is definitively not a true lattice, because absolute periodicity is absent : it is a distorted lattice. In addition to it being so distorted, it is also more or less folded : it is a disorted, folded two-dimensional lattice or net (See Figure above ), while that of real crystals is three-dimensional and not folded (and intrinsically not distorted in any other way). This (more or less folded) two-dimensional net of spiral phyllotaxy represents one layer of elements (as the only layer of elements that is present). And this layer, when interpreted as a physical layer, is, of course, three-dimensional. In crystals we have a regular stacking of a great many of two-dimensional nets (And also here, when such a net is interpreted as a physical layer of elements, it is three-dimensional). Further we should add that the 'lattice' according to which sunflowers, pineapples, branches-having-their-leaves-according-to-spiral-phyllotaxis, etc. are structured is macroscopic, while the lattice of crystals is microscopic.

In crystallization, as representative for inorganic pattern formation, something similar, as described for the formation of organic whorled structures, is going on : An initially highly symmetric medium becomes unstable in virtue of supercooling or supersaturation. It then is highly sensible to even small perturbations, which will shove off the system to a new morphology (a structure), a morphology that represents a stable configuration of the system under the circumstances. The symmetry of the resulting structure is lower than the initial symmetry, and this new structure will either be radiate (regular or amphitect), or non-radiate (Isometric crystals, Monoclinic crystals of the Domatic Class, and Triclinic crystals). We will concentrate on the former, i.e. on those crystals that represent inorganic radiate structures. And, because we want a comparison with structures that emerge as a result of phyllotaxis in plants, we only consider those radiate crystals whose main axis is -- as it is in plants -- heteropolar.

Tectology of higher plants

An individual higher plant is in fact a colony of lower organic individuals (See for this : Second Part of Website, Tectology Series ). As seen from the whole plant, which as such is a six-order individual or cormus, it is made up of a number of next-lower individual entities, namely the fifth-order individuals, called persons (personae), each of which is tectologically equivalent to a single non-colonial animal. Such a person itself is in turn built up of next-lower individuals : antimers, metamers, organs (in the morphological sense) and cells. In higher plants there are two types of person, viz. asexual and sexual persons. The former are just shoots and off-shoots, bearing leaves, while the latter are flowers. Some 'flowers', as in the Family of Composites, are themselves made up of a multitude of tiny flowers or florets, as we see them in sunflowers. Each such a flower is a person. These florets are highly integrated, resulting in one apparent flower, which itself then is already a cormus, now consisting of sexual persons only. We could say that such a composite flower is a lower-order cormus. But in a way we also can regard it as a higher-order (sexual) person.

When we do Promorphology of plants, we consider asexual and sexual persons separately, because the one and the other differ very much in structure, shape and promorph. So we consider either single shoots (main shoot or off-shoot), single flowers, or composite flowers, as to their shape, symmetry and promorph.

Promorphology of Plants with Spiral Phyllotaxis

In our Promorphological System of Basic Forms (Second Part of Website, Basic Forms, Heteropola Homostaura ) we considered structures made up by spiral phyllotaxis, provisionally under the promorphological category of the Heteropola Homostaura (regular (single) pyramids). Now we shall reconsider, and finally assess their true promorphological status.

A structure that is built up according to spiral phyllotaxis morphologically -- or geometrically for that matter -- consists of two interlaced families of spirals, according to which elements -- leaves -- are (while changing size) repeated non-periodically (Mathematically such a structure is constructed by letting elements be repeated by having them stand apart by an angle of 137.5 ... degrees along a single tightly wound (Archimedian) spiral, while dynamically such a structure is generated by successive appearance of elements at the center of the incipient structure, elements that repel each other, and, as a system of elements, expand).

Promorphology tries to express geometrically (i.e. by using a geometric plane figure or solid) the intrinsic symmetry and the number of antimers of an intrinsic material object or a part of it.

How can we geometrically express the intrinsic symmetry and the number of antimers of an (intrinsic) object that is made up according to spiral phyllotaxis? To answer this question we must consider the object's structure from a morphological or geometrical viewpoint. We then see the two interlaced families of spirals, indicating that morphologically we have in fact to do with two structures that are in some way superimposed upon each other. What structures? Well, it is clear that each composing structure in itself is a regular (i.e. not amphitect) gyroid structure (having Cn symmetry). And this can promorphologically be represented by a regular gyroid pyramid (the base of which is a regular gyroid polygon). In, say, (8, 13) phyllotaxy we have eight spirals going one way, and thirteen going the other way. So the promorph of this structure can be regarded as consisting of two interlaced regular gyroid pyramids, one eight-fold and one thirteen-fold. Generally, (a, b) phyllotaxy makes up a structure of which the promorph consists of two interlaced regular gyroid pyramids, one a-fold, one b-fold.

The next series of drawings consider the promorph involved in structures made up according to (5, 8) phyllotaxy . We then have to do with two regular gyroid pyramids, one five-fold, one eight-fold, which can, for the time being, be adequately represented by their respective bases, which are regular gyroid polygons, one five-fold, and one eight-fold. See next Figures.

Figure above : A five-fold regular gyroid polygon, representing a five-fold regular gyroid pyramid. The spikes emphasize its gyroid nature. It represents one of the two components making up the promorph of an object whose structure is constituted according to (5, 8) phyllotaxy.

And without auxiliary lines :

And as a pyramid :

Figure above : An eight-fold regular gyroid polygon, representing an eight-fold regular gyroid pyramid. The spikes emphasize its gyroid nature. It represents the second of the two components making up the promorph of a structure that is made up according to (5, 8) phyllotaxy.

And without auxiliary lines :

And as a pyramid :

When superimposing the two polygons (representing pyramids) (while retaining the auxiliary lines) we get :

Figure above : Superimposition of a five-fold regular gyroid polygon onto an eight-fold regular gyroid polygon (each representing the corresponding gyroid pyramid), resulting in the promorph of a structure or object that is made up according to (5, 8) phyllotaxis. The next Figures refine and complete the construction of this composite gyroid polygon.

Figure above : Superimposition of a five-fold regular gyroid polygon onto an eight-fold regular gyroid polygon (each representing the corresponding gyroid pyramid), resulting in the promorph of a structure or object that is made up according to (5, 8) phyllotaxis.

Figure above : Superimposition of a five-fold regular gyroid polygon onto an eight-fold regular gyroid polygon (each representing the corresponding gyroid pyramid), resulting in the promorph of a structure or object that is made up according to (5, 8) phyllotaxis. Advanced stage of the construction.

Figure above : Superimposition of a five-fold regular gyroid polygon onto an eight-fold regular gyroid polygon (each representing the corresponding gyroid pyramid), resulting in the promorph of a structure or object that is made up according to (5, 8) phyllotaxis. Final stage of the construction. The plane (composed) figure, as depicted here (green + blue), as such represents the two-dimensional analogue of the promorph of a three-dimensional structure or object made up according to (5, 8) phyllotaxy, or, equivalently, it represents the promorph of a two-dimensional figure made up according to (5, 8) phyllotaxy. The promorph (two- or three dimensional) belongs to the Dihomogyrostaura penta-kai-octomera ( = Dihomogyrostaura (5, 8)-mera), itself a species of Homogyrostaura or regular gyroid polygons or pyramids.

Figure above : Same as previuos Figure, but now drawn as a slightly oblique top view of the corresponding composite gyroid p y r a m i d, and as such representing the promorph of a three-dimensional structure or object made up according to (5, 8) phyllotaxy. The promorph belongs to the Dihomogyrostaura penta-kai-octomera ( = Dihomogyrostaura (5, 8)-mera).

Let us explain this remarkable promorph still further. Recall that the promorph of some object is the geometric figure or solid that geometrically (primarily by its shape) fully expresses the intrinsic (point) symmetry of that object, and its number of antimers.

Figure above : Regular gyroid five-fold polygon, representing a promorph that belongs to the Homogyrostaura pentamera. It has five antimers (indicated by the colors blue, green and yellow).

The second polygon is a regular gyroid eight-fold polygon representing a promorph that belongs to the Homogyrostaura octomera :

Figure above : Regular gyroid eight-fold polygon, representing a promorph that belongs to the Homogyrostaura octomera. It has eight antimers (indicated by the colors green and yellow).

When we now superimpose these two promorphs, which here means that they should penetrate each other, then we get the composed polygon already depicted earlier . As such we cannot say that this promorph and its three-dimensional analogue -- the composed pyramid -- (and with it the material objects of which it is the promorph) has a definite and single number of antimers. Its "number of antimers" is in fact its " numbers of antimers", because there are two such numbers involved, in the present case five and eight. We have an interpenetration of a regular gyroid five-fold polygon -- representing as a promorph the Homogyrostaura pentamera -- with a regular gyroid eight-fold polygon -- representing as a promorph the Homogyrostaura octomera. The resulting promorph we then asses and indicate as belonging to the Dihomogyrostaura penta-kai-octomera, where "Dihomogyrostaura" means "two homostaura", while "penta-kai-octamera" means "having five plus eight parts". The name (of the category) of the present promorph can also be written as follows : Dihomogyrostaura (5, 8)-mera.

We can let the above Figure express an object of which the elements are arranged according to a two-dimensional distorted but not folded net, as we can see such an object in the case of a sunflower, where the florets are arranged according (8, 13) phyllotaxy in a more or less plane surface. The next Figures depict the respective regular gyroid polygons, viz. the 13-fold and the 8-fold.

The next Figure shows that this regular gyroid 13-fold polygon can represent a promorph that belongs to the Homogyrostaura 13-mera.

The second component of the promorph of the above depicted object with a structure according to (8, 13) phyllotaxy, is a regular gyroid 8-fold polygon, that was already depicted earlier and which can represent a promorph that belongs to the Homogyrostaura octomera, as such already depicted above.

So indeed, because our (8, 13) phyllotaxis object (Figure above ) consists of two interlaced structures, of which the respective promorphs are Homogyrostaura octomera and Homogyrostaura 13-mera, the promorph of the object as a whole belongs to the Dihomogyrostaura (8, 13)-mera (Dihomogyrostaura octa-kai-decakaitrimera).

So with this promorph, generally taken as Dihomogyrostaura (a, b)-mera, or just Dihomogyrostaura, we cover about 80 percent of the 250000 or so species of higher plants, with respect to the promorphology of their asexual persons. So from an organic viewpoint the Dihomogyrostaura are an important promorphological category.

One might wonder, while inspecting our Promorphological System of Basic Forms (Second Part of Website), why we haven't promorphologically evaluated the above spiral phyllotaxis objects -- i.e. objects that have their structure built up according to spiral phyllotaxis, especially as we see them in many asexual persons of higher plants (i.e. shoots and off-shoots, bearing leaves according to this type of phyllotaxis) -- as belonging to the Spiraxonia (instead of to some species of Stauraxonia (namely Dihomogyrostaura) as we have done), on the basis of the presence of a generative spiral. The reason for this is that in Spiraxonia we consider the main body axis as being itself spirally wound, and in addition to that, at the same time forming a continuous spiral, like we see in Ammonites, many shell-bearing snails, etc. In plant shoots having spiral phyllotaxis, the body's main axis is not spirally wound, but intrinsically straight. Moreover, the elements that form the spiral in plants are discrete : We see separate leaves attached to the straight main axis (of an asexual person) climbing up in a spiral fashion (according to the generative spiral). So because of these facts (straight main axis, discretenes of elements) we assign asexual plant persons with spiral phyllotaxis, and also all other similarly built objects, promorphologically to the Dihomogyrostaura (Stauraxonia).

Promorphology of Plants with Whorled Phyllotaxis

Whorled phyllotaxis (or, equivalently, polystichous phyllotaxis) is observed in the asexual persons of some higher plants, and especially in many sexual persons, i.e. single flowers. Above (left image) it was depicted with respect to asexual persons of Fuchsia. Let us consider this particular example.

The next Figure gives a schematic representation of how the leaves are arranged along the stem in the case of phyllotaxis as we see it in Fuchsia, which is such that during growth two leaves appear at any one time. These two leaves then form a two-fold whorl. Then, a little higher up the (growing) stem, another pair of leaves appears. Because they are younger, they are smaller. Seen from above, they fill in the gaps left open by the leaves of the first pair. So we now have two whorls, each consisting of two leaves, which differ in size and orientation. Then, still higher up the stem, a third whorl appears, also consisting of two still smaller leaves. This goes on until the shoot finally terminates in a flower. So the result is that the asexual person consists of a stem that is provided by a series of alternate 2-fold whorls. Here we schematically depict two such consecutive whorls :

If we want to delineate the antimers of the just described structure (tetrastichous phyllotaxis), we must consider the whole asexual person, i.e. a whole shoot (without flower) of the plant, consisting of a whole series of consecutive 2-fold whorls. The cental axis of the shoot (whose stem is a narrow cone) is then its main body axis, i.e. the axis in which the antimers of the shoot meet. The next Figure indicates the domains of these antimers. There are four of them. Each such an antimer then consists of a vertical series of leaves (and the corresponding longitudinal part of the stem), decreasing in size, as we go up along the shoot.

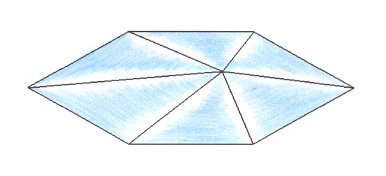

From the above it is clear that such a shoot has D2 symmetry, while having four radially arranged mirror symmetric antimers. So its promorph must then be according to the Autopola Orthostaura Tetraphragma radialia. This promorph, i.e. the geometric solid that expresses the mentioned features geometrically, is depicted in the next Figure.

And as a pyramid :

Whorled or polystichous phyllotaxis is especially common in flowers. There we often have whorls, consisting of more than two elements, for instance 3, 4 or 5. A single flower built according to polystichous phyllotaxis normally consists of four whorls : a whorl of sepals, a whorl of petals, a whorl of stamens, and a whorl of carpels. The first two whorls, and especially the second, are the most conspicuous. Sepals, petals, stamens and carpels, must be considered to be transformed leaves ( The latter are their 'ground state'). Therefore we can still speak of "phyllotaxis" in flowers ( phyllous, Greek, means leaf ). Often the number of sepals is equal to that of petals, where the petals -- when seen from above -- fill in the space between the sepals.

An individual Arabidopsis plant has, in addition to leaves, many flowers. The latter are, as its leaves, arranged according to spiral phyllotaxis. Each individual flower, however, has its components (i.e. flower organs, which are modified leaves) arranged according to whorled phyllotaxis : Such a flower consists of four whorls, first a whorl of four sepals, then a whorl of four petals whose positions are located in the gaps of the sepals. The third whorl consists of six stamens, the organs that produce pollen, while the fourth one is two carpels, which fuse to form the gynoecium with a two-chambered ovary, the female part of the flower with the eggs. The next Figure depicts all this schematically in the form of a diagram :

When we look to the above diagram depicting the organization of an Arabidopsis flower, we see that not all whorls have the same number of elements. We have four sepals, and four petals, but six stamens and only two carpels. Moreover, while the first two whorls can promorphologically be assessed as Homostaura , i.e. as regular pyramids, the third and fourth whorls must be assessed as Heterostaura Autopola , i.e. as amphitect pyramids. It is therefore not very well feasible to bring the whole flower under one common promorphological category, without losing important morphological information : The symmetry of the flower-as-a-whole must be assessed as D2 symmetry, because it possesses two perpendicular mirror planes with a 2-fold rotation axis in their line of intersection, and no other symmetry elements ( The regularly four-fold symmetry (D4 ) of the first two whorls cannot at the same time be the four-fold symmetry of the whole flower, because it is overuled by the presence of two other whorls having only D2 symmetry). So promorphologically the flower as a whole should then belong to the Heterostaura Autopola (amphitect pyramids), and the number of antimers is then as such unclear. Consequently, when doing promorphology, it is better to consider the whorls separately, except where some whorls share the same promorph. In our present case we can consider the first two whorls (four sepals, four petals) together. The promorph of this pair of whorls is then unequivocally belonging to the Homostaura Isopola tetractinota (i.e. regular pyramids with four antimers), because the symmetry of this pair is according to the group D4 , its main axis is heteropolar (while all its cross axes are equipolar [therefore Isopola] ) , and (because) it has four antimers. See next Figure.

One should not count eight (similar) antimers (four sepals and four petals), but four equal antimers, because the four petals are (at least originally) morphologically different from the four sepals, and in addition to this, they belong to separate whorls. When we consider, to begin with, only the first whorl of the flower, we have four material elements, namely the four sepals. Between these sepals there are empty spaces, resulting in an alternation of sepals and in-between spaces. So here we clearly have four antimers. The boundary lines of the latter run through the empty spaces between the sepals. And geometrically we can regard these spaces as pieces of morphology alternating with the sepals. Well, the elements of the next whorl, the petals, lie, seen from the top, precisely at the locations of the mentioned empty spaces between the sepals. So the petals just represent the empty spaces between the sepals, and thus do not as such add to the number of antimers : this number originally was four, and it remains four. So indeed the promorph of this pair of whorls (in all consisting of eight material elements) belongs to the Homostaura (Isopola) tetractinota. The next Figure depicts this promorph.

The next whorl of the Arabidopsis flower, i.e. the third whorl, consists of six stamens, arranged according to te corners of a six-fold amphitect polygon. So the promorph of this whorl evidently belongs to the Heterostaura Autopola Oxystaura hexaphragma (amphitect hexagonal pyramid with six antimers). See next Figure.

The fourth and last whorl of the Arabidopsis flower consists of two carpels, such that the symmetry of this whorl is, like that of the previous whorl, according to the group D2 (two perpendicular mirror planes and a 2-fold rotation axis coinciding with their line of intersection). There are, however, only two antimers present, so the promorph of this fourth whorl is belonging to the Heterostaura Autopola Orthostaura diphragma (rhombic pyramid with two antimers). See next Figure.

Promorphology of Plants with Alternate Phyllotaxis

Alternate phyllotaxis (or, equivalently, distichous phyllotaxis) is observed in the asexual persons of some higher plants, like maize. See Figure above (right image) .

Unlike in whorled phyllotaxis, but like in spiral phyllotaxis, structures built up according to distichous phyllotaxis are not easy to assess promorphologically. Here the leaves occur one at a time at fairly regular intervals, with nearest neighbors on opposite sides of the stem. As has been said, a familiar example is maize (corn), as shown in the Figure just referred to. This mode of phyllotaxis is typical of grass species, and there are a great many of them. Therefore it is morphologically important and interesting what promorph is exactly involved in distichous phyllotaxis. Like we had in the case of spiral phyllotaxis, we must recognize a composed promorph, i.e. two simple promorphs that partly mutually interpenetrate. This is because this mode of phyllotaxis involves a translational element, which is alien with respect to point symmetry (because a translation moves all points, while in point symmetry at least one point stays where it is during a symmetry transformation).

If we focus on one leaf, together with the corresponding parts of the stem, above and below that leaf, i.e. if we concentrate on only one metamer of the maize plant (Figure above (right image) ) :

Just above we indicated a leaf, together with parts of the stem above (half way up to the next leaf) and below (half way down to the next leaf), as a "m e t a m e r" of the maize plant. It is probably better to consider two consecutive leaves together with the piece of stem between them as a genuine m e t a m e r of the plant, because this unit is exactly repeated (apart from a slight and gradual decrease of size) along the plant's main axis.

A metamer is a sequential part, and represents some lower-order individual, that, by repeating itself along the body axis, constitutes, in the case of a plant, a shoot (person), while an antimer is a counterpart, representing another type of lower-order individual, that, by repeating itself a definite number of times around the body axis, constitutes, in the case of a plant, (also) a shoot (person). And a person itself is, in the case of many plants, in turn a lower-order individual, that by repeating itself (mostly irregularly) constitutes the whole plant, which is then, generally, called a colony or cormus.

For this doctrine of subordinated individuals in plants, but also in animals, which doctrine is called Organic Tectology, see Second Part of Website, Tectology Series .

If we look, from above, down to an asexual shoot or person of a maize plant, i.e. if we project this asexual person (stem plus leaves) onto a plane perpendicular to the main axis of the shoot, then we see D2 symmetry, namely two perpendicular mirror lines, and a 2-fold rotation axis coinciding with their point of intersection. We see also two antimers, separated by one of the mirror lines (where one antimer consists of a projected column of leaves all positioned on one side of the stem, and the other antimer consists of a projected column of leaves all positioned on the other side of the stem) :

Because of the alternate position of the leaves, resulting in 1-fold 'whorls', the mirror plane corresponding to the mirror line b (and with it the 2-fold rotation axis) of the projection vanishes, as soon as we undo the projection, i.e. when we just consider the shoot in its full three-dimensionality. We then have a structure with only D1 symmetry. And the only mirror plane left over (corresponding with the mirror line a of the projection) does not separate opposite leaves, but the right and left halves of them. See next Figure.

So not only half a rhombic pyramid (having one of its (three) sides vertical, i.e. parallel to the pyramid's main axis, as depicted earlier ), but also a bilateral three-fold pyramid, can represent one half of the basic form of the Autopola (Orthostaura). And although such a pyramid has only one mirror plane (instead of two, as in the Autopola), and thus promorphologically belonging to the Allopola, it should, in the present context (and only in the present context), show that it is not just formally derived from Autopola (by halving), but that it is derived from them in such a way that it did not totally loose the characteristics of the Autopola. We can do this by letting such a pyramid promorphologically belong to the Autopola by calling the category of its promorph

The next Figure gives a slightly oblique top view of a pyramid that results from the above specified interpenetration of two bilateral 3-fold pyramids.

The next Figure gives this same result, but now showing even more clearly that it is a pyramid composed of two pyramids (blue and red).

The Figure just given, thus depicts the promorph of our asexual shoot of the maize plant. This promorph then belongs to the Autopola Orthostaura di-monophragma and is again depicted below (where we did not apply the usual colors (green, yellow) to indicate the two antimers, but the colors blue and red, because they make the image more clear.

This concludes our discussion concerning the assessment of promorphs of plants with, respectively, spiral (astichous), whorled (polystichous) and alternate (distichous) phyllotaxis.

In the next document we will investigate inorganic whorled structures as we see them in snow crystals (snowflakes).

e-mail :

To continue click HERE for further study of the Theory of Layers, Part XXX.